Why and how does the knife lose its sharpness?

As a result of contact with the material being cut and its reaction, steel particles come off from the blade’s cutting edge, thereby changing its shape. And this process is quite active, mostly because of the enormous concentration of effort on a very limited surface – tearing something that sticks out is always much easier.

Damage occurs at two levels – micro and macroscopic. Microparticles come off as a result of friction. The softer the steel of the blade and the harder the material being cut, the faster this happens.

An unnamed mild stainless steel knife with which we will try to plan a solid seasoned wood will dull much faster than a signature knife from a skillfully hardened ultramodern super steel with which we will cut only tomatoes. Of course I mentioned completely extreme cases. But if the process of changing cutting edge’s shape and the loss of sharpness associated with this would be limited only to this – oh, how rarely would we have to sharpen our knives, even the poor-quality ones!

Given the hardness of tomatoes, there is practically no difference between the deterioration resistance of the best and worst knife steels. Even with solid wood it would not be too much trouble if wear on the cutting edge was limited only to the above mechanism.

Unfortunately, the problems do not end there. No cut material is completely homogeneous – even in tomatoes there are softer and harder areas (although all of them are much softer than the blade). But not only tomatoes are cut with a knife!

The difference in hardness of parallel fibers of wood and the resinous knot in it is already much larger. And the superiority of steel in hardness and mechanical strength over the mentioned knot is already noticeably less (especially if this steel is not from the highest category).

But that’s not all! There are many materials that contain even harder insides than material itself, and in some cases even more than steel blade.

Take at least packing cardboard, and the most primitive sand contained in it. He gets there by simple carelessness – who will diligently clean the starting materials in the manufacture of something so cheap! And they can intentionally add sand, especially if they measure the sale by weight.

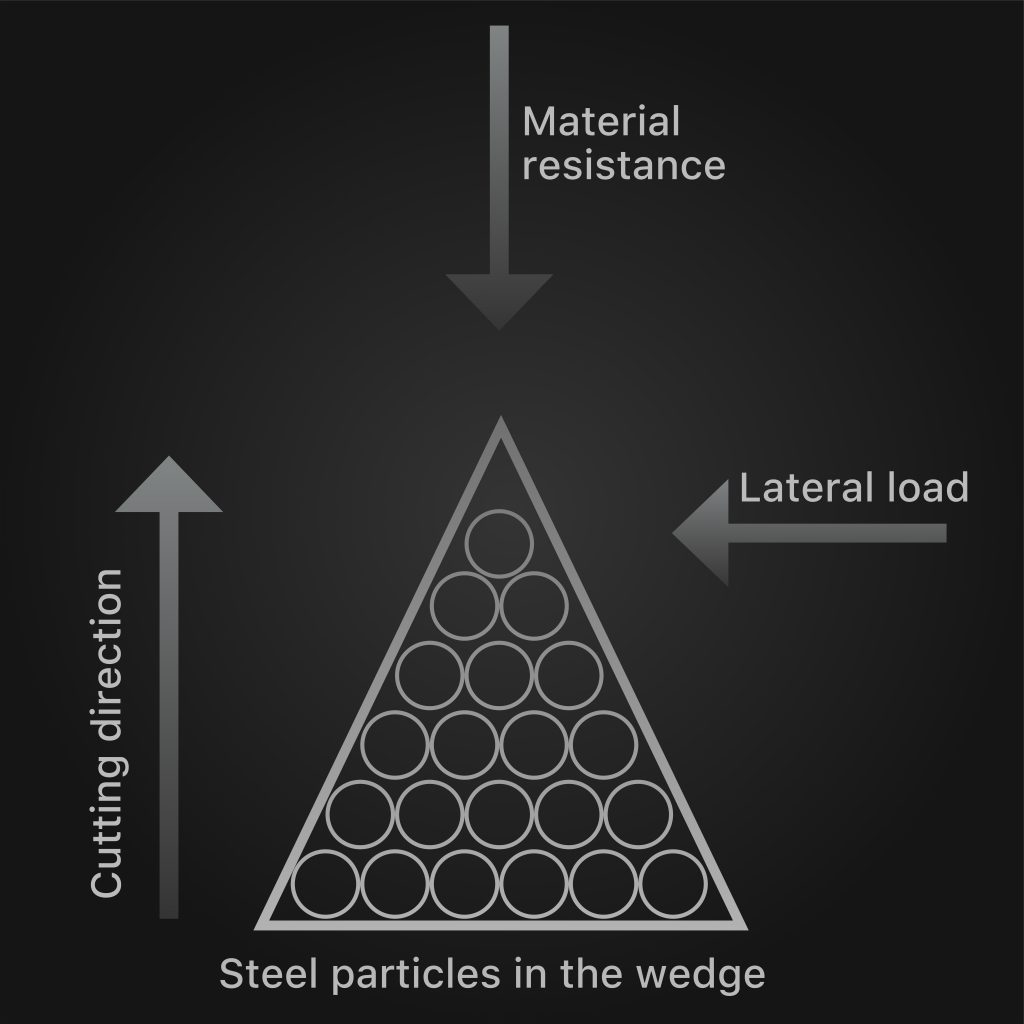

Sand is crystalline silicon oxide, and grains of sand are much harder than even the highest quality knife steel. When the thin tip of a cutting wedge meets a grain of sand in its path, it cannot cut it and therefore pushes it to the side. But even the blade itself experiences a lateral load, the counter force has a lateral component that can slightly bend the very top of the cutting wedge.

The better the steel of the blade, the less the edge bends. With a very good blade and a very small grain of sand, the cutting edge will return to its place after bending. And if the steel is worse, or the grain of sand is bigger, then the edge will bend a little.

Exactly the same thing happens when the blade takes the force not quite in the symmetry of the cutting wedge – for example, when meeting a harder knot in the mass of wood the fibres of which are directed at a different angle. Here a lateral component of the load on the cutting edge also appears.

And the human hand never leads the blade exactly forward, so that the force falls on the cutting wedge strictly in the plane of its symmetry. In real cutting, the cutting edge is regularly subjected to random lateral loads, as a result of their impact, it loses its straightness, and the wedge forming it is in the right shape.

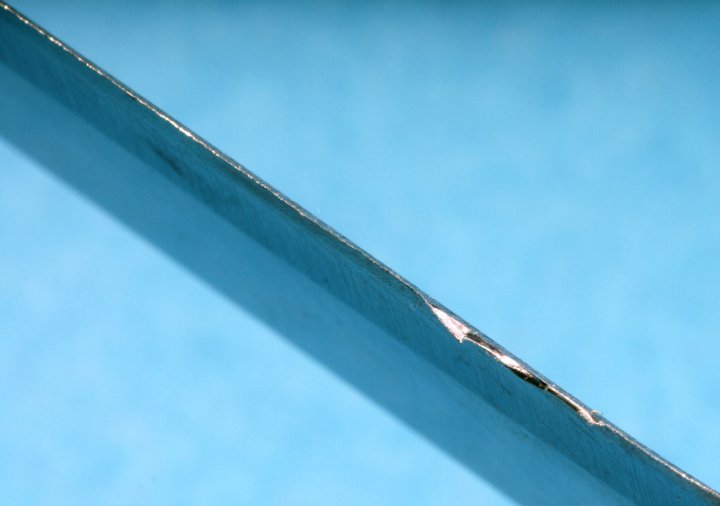

Its apex deviates from the plane of symmetry and after that even with perfectly correct cutting of a relatively soft material takes on a bending load. And the further the edge deviates, the greater this load becomes, since the bending moment increases – and as a result, the edge deviates even more. By itself, it will not return to its place – the cutting wedge has already lost its stable form. In the end, at a certain bending angle, the wedge tip will simply break off, leaving a much wider surface in its place. The cutting efficiency will immediately decrease – in other words, the blade is pretty dull.

Of course, the bending angle at which the tip of the cutting wedge breaks or bends depends on the properties of the steel and the quality of its heat treatment. It is significant that the cutting edge’s wedge of itself will never return to its original, stable position, ensuring optimal cutting quality.

Another, absolutely exceptional mechanism for the loss of sharpness is damage to the cutting edge caused by knowingly misuse of the knife.

For example, some users like to engage in demonstrative cutting of metal nails. The nail, of course, is noticeably softer than even the inferior blade – in any case, it is a third-rate alloy with a very low carbon content and without any heat treatment. But their hardnesses are already comparable, after all, this is an iron product, besides thick, massive, especially in comparison with the thin cutting edge of the blade.

Absolute strength is the sum of the relative strength (quality) of the material and its quantity. With a thick linden log you can break a thin bar of stained oak.

So here – the cutting edge of a blade made of bad steel simply hesitates, hitting a slightly softer, but much more massive nail. A good blade is likely to cut the nail, but some of the steel will also crumble out of its blade, and some will hesitate, leaving a fair chipping, which will be quite difficult to remove.

If a very sharpened blade of excellent quality is dropped from a height of 15-20 cm with a blade perpendicular to the edge of the glass, then a notch will remain on the blade, even visible with the naked eye.

Therefore, good advice comes next: never throw your kitchen knives (and they, as a rule, have blades made of not too hard steel and sharpened rather thinly) into a metal or along with the rest of the dishes. Gently wash them in your hands, wipe them dry and set aside. Do not throw them also in the kitchen drawer – there their blades will also beat against each other and other devices. Store the knives separately in a wooden base unit or on a wall on a magnetic holder.

And throw away all sorts of newfangled glass and porcelain cutting boards – cutting them blunts knives instantly! Limit yourself to plastic or classic wooden boards.

And do not ask yourself the rhetorical question “why then do these boards are made and sold, since they spoil the knives?” Apparently, for this they are made and sold in order to spoil your knives. To keep the knife as short as possible, so that you have to buy new ones more often.

Yes, and a wooden board itself, if it is good, can serve for years, and most people will break a glass or porcelain in a few months by accidentally dropping it from a cutting table onto a tiled floor. That business is spinning.

And all the stories and advertisements about the “self-sharpening” blades can be safely attributed to the field of science fiction, which is also completely unscientific.

Leave a Reply